Being a Labor and Delivery Nurse Converted me into a Freebirther

Breaking free from safety and other (ordinary) horrors

At this point in my female life, I view birth as a sacrament, a “visible form of grace.” Birth is a ceremonial act, an experience of rightness and beauty for a woman. It is the ultimate act of female physiology. For millennia, birth was a female tradition handed down through generations of women whose bodies stored the knowledge in their bones. This female tradition deserves to be cherished but Western culture seeks to strike it down. Our culture embraces a medical model of birth—where outsiders, experts, and hourly workers deliver your baby. Birth isn’t treated as tradition but as a procedure. In the hospital, the tradition is procedure. And as a hospital Labor and Delivery nurse I witnessed the countless ways a hospital takes a divine ritual, desecrates it and makes birth obscene.

Exhibit A:

C-sections are currently the most commonly performed surgery in the world. A few highlights on this situation:

Over 1 million births are delivered by cesarean every year in the US

The cesarean delivery rate in the US rose from 5% in 1970 to 31.9% in 2016

The rate of cesareans varies widely between hospitals with some rates as low a 7.1% and others as high as 69%

The maternal mortality rate in the US is approximately 2.2 per 10,0000 cesarean deliveries. Though this is overall low, it is significantly greater than for vaginal delivery which is approximately 0.2 per 10,0000

I wasn’t aware of these facts about cesareans until recently, although I could have intuited it from having helped facilitate several. It depresses me but doesn’t shock me. Cesarean sections are the birth equivalent of fast food. In the sense that everything is on a timeline, everything has its order, everything is automated and functions like a well-oiled machine. Perhaps this is a comfort to some women. They desire a mechanical approach to birth with maximum efficiency.

I can only assume this desire comes from long-held subconscious beliefs forged in their inner landscapes by media and academia alike. I, however, prefer my birth to be organic, untouched by the machine. This is partially due to the fact that I used to be a part of the Machine.

If you have spent any amount of time on the Natural Birth Internet™, you’ve probably read the “list of hospital things that disturb birth” typed out many times. Bright lights, weird smells, strange people, whirring machines the list goes on. I think we can all read these things and deduce that yes, they sound likely to disturb our mammalian processes needed to give birth naturally. Yet, when you are regularly immersed in the things on that list, it is another thing entirely. Especially when you are the strange person, you are switching on those bright lights, and you are witnessing strange things. Not only is natural birth disrupted, but the ability to naturally support birth is as well—no matter your good intentions.

I did not last long in the realm of the Labor and Delivery, but I lasted long enough to see what I needed to see in order to make me forever recoil at the idea of voluntarily giving birth at a hospital for anything less than a true emergency.

I began working as a Labor and Delivery registered nurse in 2016. It was a few years into my nursing career and I was looking to transfer out of a med-surg unit (the department that most of the hospitalized patients come through) that was making me miserable in innumerable ways. It was a place where I found myself crying regularly, where male patients attempted to sexually assault me and other female staff, where drug seekers screamed in my face, and where some of the doctors spoke to me like a lesser life form.

I needed a change.

I had given birth once at this point in my life, in a hospital. It wasn’t great. I had an unnecessary episiotomy cut, everyone yelled at me to hold my breath while I pushed on my back. I didn’t know the doctor who seemed annoyed to be there to “deliver” my baby. Hospital staff injected me with Pitocin postpartum as a matter of policy and without consent. A nurse handed formula before I even breastfed. Another nurse bathed my baby right after she was born.

Thankfully, my brain didn’t code the birth as horribly traumatic. It was just another chapter in the tale-as-old-as-time unfortunate hospital birth story. And you know what this means—I wanted to be one of the ones to “change the system from the inside”! Hence my career pivot straight into hell.

Why does birth not belong in the hospital?

Let’s start with cervical checks, many of which are forced on patients. For those lucky enough to not know what a cervical check is: it’s when a medical provider inserts their fingers into the vagina and probes the cervix to see if it’s dilated or softening during labor. These exams are used as some sort of predictor of how the birth is progressing. They are also painful, invasive, and largely useless

I once was taking care of a young teen mother. She had been sexually assaulted but decided to keep her baby. She was extremely fearful of cervical checks, and with her age and history, this obviously checks out. I think all women would be wise to avoid them, and would be reasonable in fearing them, but this situation in particular really illustrates the barbaric nature of the practice. The male doctor I was working with was absolutely adamant that I check her, simply because he was curious about how her labor was ‘progressing’. After discussing it with him and seeing her tearfully say no, I refused to. Frustrated, the doctor barged into her room and talked her into it so I tried again. She started to cry and I refused to continue.

I now know that the cervix is an actual portal that should not be pried at and manipulated. The only person who should be touching the cervix is the mother. It’s a testament to the power of the industrial birth machine that this fact is something I had to remind myself of and that all of the bullshit about cervical checks being “just a thing that we do” had to be unlearned. This is part of an absolute OBSESSION hospital staff have with measurements during labor. This because they do not trust the female body. Even if, like me, they had some notion of a woman’s intuition about her body during birth, that’s all scrubbed from their systems in medical and nursing school.

In the Labor and Delivery department, the female body is merely one components in an equation that results in a baby and if there are any numbers that hospital staff can glean from her, they want to, regardless if it is actually “evidence based” or not. It should go without saying but curiosity doesn’t validate coercion.

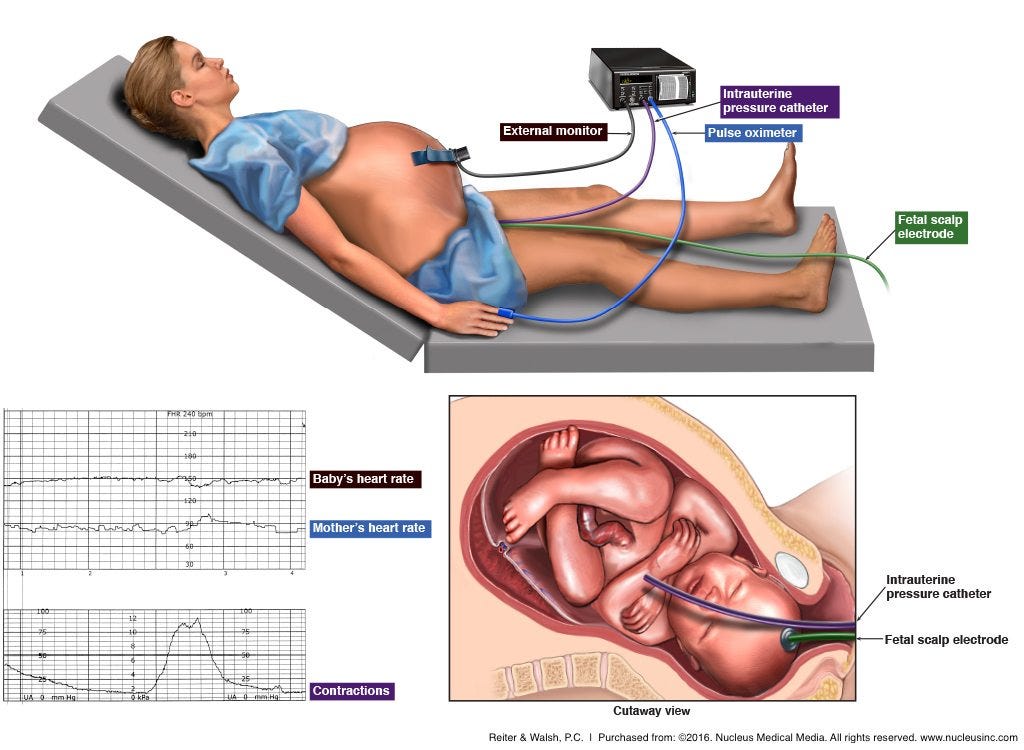

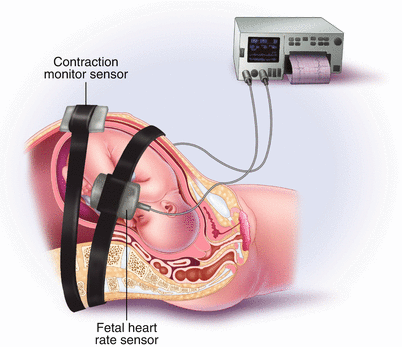

Another coercive tool of obstetric curiosity, and my most loathed, is the Intrauterine Pressure Catheter (IUPC). It's a plastic cord that’s snaked through the woman’s cervix and then pushed into the amniotic space so it can measure the strength of the mother’s contractions. This device came into popular use because the tocodynamometer—that strap you often see looped around the mother’s belly—does not give very accurate measurements. So the catheter, despite being more invasive and carrying a higher risk of infection or bleeding, became the preferred tool of measurement for certain inpatient situations. Another internal monitor that is almost always paired with the IUPC is the Fetal Scalp Electrode (FSE). These are little spiral wires that you literally screw into the presenting part of the fetal scalp in order to get more accurate fetal heart tone readings.

During labor nurses and doctors pay more attention to the fetal heart rate than to the actual woman whose body is being monitored to create that paper strip. I imagine this is because that tactile piece of paper, that image with what looks like definitive numbers and lines, is something tangible to hold onto at a time that feels uncertain and unknown.

How were babies born without plastic tubing, electrodes, and pints of synthetic hormones coursing their mother’s bloodstream in the past?

How was a woman’s progression through birth measured?

What are measurements really?

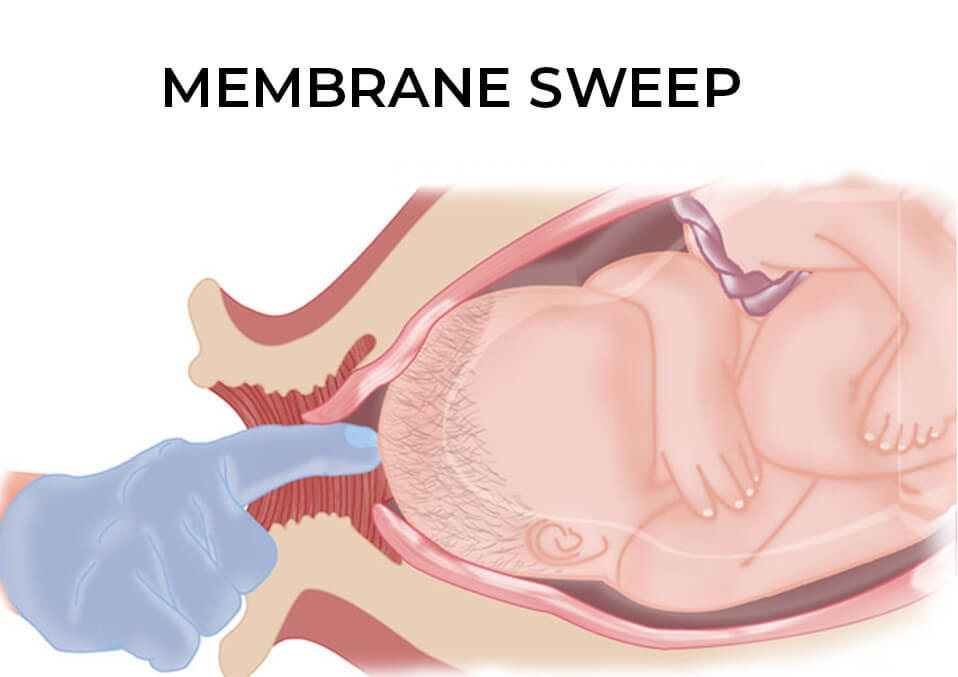

Measurements are scale on which to place the woman, a way to rank her progress and her level of adherence to what the medical model considers normal. Which is why I often saw “Ineffective Contraction Pattern” listed as the reason for more invasive interventions like artificial rupture (“sweep) of membranes, a balloon to dilate the cervix, or Pitocin.

Meanwhile, the belt they fastened to a mother’s belly during labor to monitor contractions is widely to known to have a pitiful 73% accuracy rate. How can a doctor determine if the pattern of contractions is “effective” if they are not using a reliable means of measuring them? And more importantly--why are we measuring anything in the first place?

The answer is comfort and not the comfort for mother or the baby, but of their managers. I say “managers” because that is what Labor and Delivery staff were.

I said above that it’s impossible to provide natural birth support in the hospital setting and this is why: the policies and patterns of obstetrics create a dynamic in which medical professionals are not facilitating a supportive environment for motherbaby, rather they are creating an environment in which the “care team” is comfortable with a series of potential events and interventions.

There is a line in Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, where Aunt Lydia, one of the dystopian regime’s principles in charge of indoctrinating the new handmaidens into their roles of surrogates, describes the changing notion of freedom:

“There is more than one kind of freedom,” she muses, “Freedom to and freedom from. In the days of anarchy, it was freedom to. Now you are being given freedom from. Don’t underrate it.”

This is how I think about the ‘safety’ of a hospital birth. There is safety from and safety to.

For the healthcare worker, there is safety from litigation, from a sense of personal responsibility, from failed interventions and their consequences. As much as I am railing on my own profession here, we are of course people (in nursing, primarily women), and we are people who, of course, are not particularly keen to handle or be a part of tragedy. In essence, it is safety from the lawlessness that is birth.

In a hospital birth, the healthcare worker has safety to work in a way which they believe creates the most “success”, to create environments that benefit those practices and create the most ease in checking off their to-dos, to luxuriate in the aforementioned multitudes of measurement of the female body.

My ambitions to effect change were a fantasy. In my naivety, I failed to realize that nurses are nothing but female blue-collar workers in a giant system that has no true alliance to them. Nurses are a dime a dozen to hospital systems, and in the day to day work that goes on there, our individual impact (good or bad) may be great on our individual patients but it has no great bearing on the way things happen in that hospital. Not only did I fail to understand this fact, but I failed to understand another, more important fact: birth typically doesn’t even belong in the hospital in the first place.

You may be aware of the recent news stories about how pelvic exams are performed on unconscious, sedated women as a matter of routine in medical school training. The practice, still legal in 29 states, is common in medical schools and teaching hospitals. These ‘exams’ are most often conducted when the woman is unconscious for surgery. After the surgeon has performed a necessary exam the students, without the patient knowing, repeat it. During my nursing career, I managed to avoid being in a position where I had to perform an unconscious exam but there is an enormous amount of pressure placed on students to perform any exams that are asked of us by our seniors, by our residents, by our attendants. And if we're not comfortable with the exam, it's difficult to say no.

I bring this up here because this practice of unconscious exams, reminds me of my training in how to place invasive tools like Intrauterine Pressure Catheter and the Fetal Scalp Electrode. I was trained on inserting these modes of measurements while my patients were at their least coherent. The nurses who trained me joked about only practicing on women who were “epiduralized”, insinuating that as they couldn’t really feel what was happening so it really didn’t matter too much. Another line from Aunt Lydia occurs to me, “this may not seem ordinary to you right now, but after a time it will. This will become ordinary.”

I was told to place these interventional objects of violation into women whose situations didn’t absolutely necessitate their use. It was done with a flippant attitude by the other RNs who were used to these things, but I was left reeling. The utter disregard for the human tissue we were manipulating felt off in the worst possible way.

Manipulation. That’s the crux of all of this. Manipulation and desecration, born of mistrust and fear, manifested through practices of safety, both from and to.

During my time in Labor and Delivery, I worked overnights and we often started inductions on night shift by placing a cervical ripening agent and allowing the woman to rest as best she could overnight, hopefully progress, and then in the morning when the doctors arrived, we’d start pitocin, and possible an artificial rupture of membranes preformed by the doctor.

If all went well, the women would go on to give birth during day shift while the doctors were present. All did not always go well though— especially when women came in with “unfavorable cervixes.” Unfavorable would mean closed and high and uneffaced, or only a little bit of one or two of those things. This is anecdotal, but in manipulating the body in that state, I often saw the body push back. Babies also don’t like this manipulation, they often didn’t tolerate the contractions that accompanied the cervical ripening agents, and crash c-sections happened. I found myself walking out of work asking myself “what did I just take part in?”

Every part of me knew we were toying at something that is bigger than any one of us, and often to the every part of me knew we were toying at something that is bigger than any one of us, and often to the disadvantage of mothers and babies alike.

I finally hit my limit when I witnessed an external cephalic version (ECV)—a rudimentary procedure where doctors push down and twist on a pregnant woman’s belly to try to get her baby in the head-down position for birth.

To “relax” her womb and “ease” the baby into the “correct” position, the mother is given a shot of Terbutaline that can send her heart rate soaring or as the doctors described it “a sense of nervousness”. This particular mother wept and begged for it to be over as the doctors bore down on her quaking body. The baby stayed in breech, and she was wheeled off to have a C-section. I had cared for her several times as she came in to triage a lot, and had wondered if she had an intellectual disability. Seeing her in so much pain all due to an unnecessary procedure that I’m not entirely sure she could truly consent to was too much to bear. It was the cruelty of the whole thing and the fact that no one else seemed to view it as cruel.

I found myself constantly questioning if I was too sensitive or anxious or weird because I seemed to have extreme emotional reactions to ‘routine procedures’ that other staff seemed to not even take note of. I had recurring nightmares about hemorrhages and emergency cesareans and babies with head injuries from forceps or vacuums. Seeing operative vaginal deliveries facilitated by those means wrecked me emotionally and very viscerally made clear the fact that this was an environment of disregard for babies and mothers as fully human. It was like they were merely the projects we were managing.

The way in which these “projects” were managed became more and more glaringly disgusting to me. The way the (almost all male) doctors would massage the perineum of women while they pushed in a garish show of control, shoving their sterile-glove clad fingers doused in soap into vaginas that were often so numb the woman was none the wiser. The way women were laid out on display, often unable to move much, with so many hands prying at them while they attempted to do their most intense work. The way babies were pawed at and aggressively stimulated immediately after birth despite the fact that they were crying or even just a little shocked. Needles being jammed into the umbilical cord minutes after birth. The way placentas were thrown out like trash.

I quit.

I quit and the amount of relief I felt was immense. I stopped having nightmares. I quit and I felt grateful for the women who invited to witness undisturbed birth, for the babies I was allowed to hold, for the experience exactly what our fading birth traditions are up against. I quit and I felt shameful for my own part in traumatic experiences or less than ideal situations some women endured when I was a member of the team caring for them. I quit and not only that, but I chose to freebirth twice in the years that followed. Not only because of the things I saw but of the things I didn’t see.

What I didn’t often see in hospital birth was true dignity afforded to mothers, the women entrusted with the raising of the next generation, the women whose hearts and hands would go on to wipe tears and read stories and hold little faces to their own in awe. What I didn’t see in hospital birth was any sort of consideration for the female body as a powerful agent of action and keeper of wisdom. I saw fear and annoyance and a rivalry with it. What I didn’t see in hospital birth was respect for physiological timelines or processes. There was always some pressure, some underlying rush, even when it wasn’t spoken out loud. What I didn’t see recognition of just how special birth is. Birth was just an everyday part of the job.

I simultaneously understand that not every women can or wants to give birth at home. As a nurse, I know there are medical circumstances that truly warrants utilizing the hospital, I am no stranger to this fact. And yet, I am in this unique position of really knowing what both hospital birth looks like and also knowing what sovereign birth is like. I would choose birthing at home, whether with help or not, over and over. The dignity I need to uphold for myself is accessible at home, in my own space. Likewise, the wisdom of body is infinitely more accessible to me at home and without people staring at me expectantly. At home, there is no timeline to adhere to at a time when time itself seems so irrelevant and fake. At home, the specialness of birth is obvious and remains a sacrament.

Thank you for sharing my writing here. My hope is for women to see this and get an understanding of the foundational truth of what the medical system is-it is a system. It is based on procedure, it has does things according to how “things are done”-it is an organized framework of people and machines and policies that functions to make a profit and protect providers.

All of this before it is a place for your humanity to be recognized and your birth plan to be honored. If you experience those things, I am grateful for that and I know it does happen-but that is the exception, not the rule-and that is not only due to the fact of healthcare being a “policy and procedure” factory but also due to just the basic needs of the women and baby in a physiological birth, which the hospital setting just cannot provide due to it’s basic nature.

I birthed five children, and only the first was in the hospital setting, with a doctor in attendance who was supremely patient and non-invasive.

This was in the 70’s, when the invasion on the mother’s territory was not so extreme, but even so, he was enough of a free birther (also willing to attend home births) that the medical association kicked him out and he lost his OB hospital privileges.

Hundreds of his patients/clients demonstrated in support to no avail. Without the option of attending births that might have to move to the hospital, he had to stop the obstetrics altogether, and my last home birth was with a nurse midwife attending, which was probably for the good, too.

Back then, so many of us were pushing back against the desecration, but any gains we made seem to have lasted only a generation. I was surprised to learn how super technical and complicated an uncomplicated birth had become, when with my daughters as they gave birth in hospitals, and saw them deal with various levels of management.

I am grateful to you younger women who are speaking out and resisting and protecting your own selves and families from this abuse, and I’m weeping for all the mothers and babies (and nurses) who continue to suffer in countless ways under this dreadful system.